Project Update

I have completed my in-person research and case studies on groups of financially underserved individuals across the Southern USA. The project chosen came from my experience running my fintech company, CapWay, which focused on providing digital financial services and tools to the financially underserved, specifically unbanked and underbanked individuals and those defined by the working poor, also known as living paycheck to paycheck. From that, I was able to confirm that published data, even from the biggest banks and research firms, was often not truly reflective of this audience. My focus as an ambassador was to dive deeper by investigating the key reasons why, understanding behavior and mindset, and the ultimate impact of being financially underserved.

During my project, there were moments of discovery that further supported my thesis about skewed data and why that had reflected missed or needed opportunities in the world of digital financial technology and inclusion. However, there were also challenges along the way in making it happen.

Starting with the challenges, it was very important to me to conduct these case studies in person rather than virtually (e.g., Zoom or similar). The energy of having those who participated in the research group feel that they were there not just for research but because I cared, and also to be in the room with others who were dealing with similar issues, and therefore knowing they weren't alone. Although the in-person component was paramount and I wouldn't change it (and won't, as I plan to continue this research), it was a challenge. In certain cities, even with the help of trusted local organizations, finding participants wasn't easy. Was the population of people I was targeting there? Yes, for sure. But getting them to participate in a case study wasn't the easiest task. Sometimes, even confirmed participants didn't show up. Moreover, I found myself doing more one-to-one case studies than I originally planned, but I was okay with it because the information was still highly valuable. In some of those cases, I agreed to keep the person's identity hidden because they were fearful and didn't want their information disclosed in any way, even though I informed them it would be used only for internal purposes.

Photo of me and two participants after the case study in Washington, D.C.

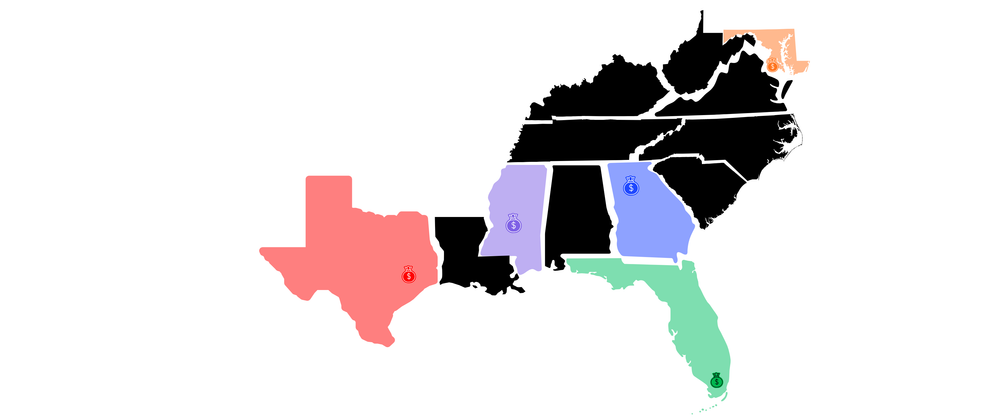

On the plus side, I talked to roughly 50 people across the following five cities: Houston, TX, Jackson, MS, Miami, FL, Atlanta, GA, and Washington, D.C. Each of my case studies followed a similar line of questioning, although overall, each varied because conversations would naturally flow, and each conversation was different. In those conversations, we discussed why they were unbanked or underbanked. Some participants were unbanked due to circumstances: they had a bank account at one time but, due to overdraft fees, their accounts were closed, and they haven't been able to open another one. For others, their reasoning ranged from a lack of access (no banks in the area, can't get one due to no birth certificate or license) to simply not trusting the system and banks (and a preference for being able to physically touch and see their money).

Doing these case studies at a time when many in the U.S. are financially struggling made many of these conversations even more interesting. Some of the participants were "homeless" in the sense that they (and their kids) were living in a cash pay-per week hotel, some relied on food pantries for food, others talked of how they owed money so if they did have a bank account (required by their employer) they monitored their account so that second money hit their account, they withdrew it because they were scared the bank or someone else would take it.

Overall, the case studies were eye-opening, even to me as someone who has worked with this target audience for years. I started each case study by informing each person that I wanted them to be honest. Raw and honest. I wasn't there to judge. I was there to listen, take the results of this research and learning, and figure out how to make the world of digital financial inclusion work for them by working with them because their words, circumstances, and needs matter. As mentioned earlier, I plan to continue this research, and my time as an ambassador at Interleder and this research have laid the foundation for further research and the opportunity to find even more ways to stand on data in the fight for even better digital financial inclusion services and policies.

Progress on Objectives, Key Activities

My research project was broken down into three goals aimed at examining the lived financial experiences of underserved individuals in the Southern United States, defined as those who are unbanked, underbanked, or excluded from the traditional banking system. It also engaged key stakeholders and compared on-the-ground findings with existing financial research to uncover gaps, biases, and opportunities for more effective financial inclusion solutions.

Each goal included specific objectives that supported the project's overall outcomes.

Goal one, which defined and understood the financially underserved, included the most objectives, as it was foundational to the research. The first objective was to clearly define and quantify the target audience. I initially accomplished this by leveraging existing data (found here and here) that identified cities with high populations of financially underserved residents. These cities became the top candidates for in-person case studies.

Once cities were selected, participants were recruited either through social media outreach or partnerships with local organizations that already worked with the target population. Participants self-identified as unbanked, underbanked, or working poor, and in some cases, this was confirmed through an application process. For example, in Atlanta, GA, we partnered with Goodr, which distributed our Google Form application to potential participants through their email list. As part of that application, individuals selected which of the three categories they identified with. This identification process was also reiterated through opening questions during each in-person case study.

One evolution from the original objective was that, in later cities, we expanded participation to include individuals who could speak to being subject to "Black tax," the financial pressure to support extended family or community.

The remaining objectives under goal one focused on a deep understanding of participants' financial reasoning. Much of the questioning centered on why individuals were financially underserved and why/if they remained so. A consistent response was trust. Many participants expressed deep distrust of banks and the broader financial system, often rooted in personal experiences or negative experiences shared by friends and family.

When discussing financial behaviors, such as money management, credit access, and transaction methods, many participants shared that they weren't too concerned with participating in the formal financial system. Several preferred cash-only lifestyles when possible and felt comfortable operating outside of traditional banking structures. Access to credit was rarely a priority unless it was tied to a major life goal, such as purchasing a home, but they were okay with renting.

Goal two, which focused on financial technology and inclusion, along with stakeholder perspectives, had the primary objectives of assessing how efforts impact this population, gathering cross-sector insights, and developing actionable recommendations to improve financial access.

These objectives were met through three main approaches. First, I conducted interviews with fintech founders working directly with underserved communities, including Evan Leaphart, CEO of Kredit Academy, and Dana L. Wilson of CHIP. These conversations explored the advantages and limitations of digital financial products, adoption challenges, and where fintech founders are succeeding or falling short in serving this audience.

Second, questions related to fintech and digital financial services were incorporated into each case study. Toward the end of every session, participants were asked which fintech apps or services they currently used and, if they could design a fintech product tailored to their needs, what it would look like. Most participants reported using at least one fintech app, most commonly Chime or Cash App. However, none reported using fintech tools for budgeting, investing, or financial education. Even with the fintech apps, many responded that they didn't think the apps were actually working in their favor. However, they were a better alternative than the traditional bank, almost to the point of choosing the lesser of two evils.

The third approach involved speaking with policymakers and leaders from partner organizations. One example was Yasmine Salina of Hustlers Guild in the Washington, D.C. area. She shared that many individuals served by her organization do not have bank accounts, but that opening an account is often not the hardest part. The greater challenge is that many lack the documentation required to open an account, such as a birth certificate or government-issued ID. Securing these documents can require hours of hands-on support for a single individual, which is work that her organization regularly undertakes.

Goal three was focused on analyzing and comparing existing financial research to identify data gaps, inconsistencies, and under-explored opportunities in financial services. Satisfying the objective overlapped with case study questions, particularly when participants were asked what types of digital financial products would actually serve them.

One major gap identified was that many financial inclusion products have been built for underserved communities rather than with them. Too often, products are designed by founders, banks, or venture capitalists with assumptions rooted in capitalism-first thinking and in what they believe this audience needs, rather than insights from sustained, on-the-ground engagement, such as the in-person research conducted in this project.

Additionally, part of satisfying this goal involved intentionally creating a comfortable space for honesty. During the opening remarks of each case study, participants were encouraged to be completely transparent, with no answer considered too honest or raw. These conversations revealed realities that are often absent from traditional data sets.

For example, during the Jackson, MS case study, I asked participants, "What is the most expensive item you've ever purchased, and why?" One participant responded that he had purchased a Louis Vuitton bag. His reasoning was that the brand represented status. He always saw celebrities and rich people carry it. Once he saved enough money, he made the purchase. He admitted that the money could have and should have been used for something else, but the ability to have that status symbol mattered more. My follow-up question was, "Where is that Louis Vuitton bag now?" His response, "I sold it for drugs."

This moment underscored how existing research often fails to capture the complexity, contradictions, and emotional drivers behind financial decisions, highlighting the importance of qualitative, community-centered research in shaping more effective financial inclusion strategies.

What impact does the project have on your perception of digital financial inclusion?

The research from this project is intended to benefit both individuals in financially underserved communities—specifically those who are unbanked, underbanked, and part of the working poor—and the decision-makers and creators developing digital financial inclusion products and services. For many participants, this research provided a platform to be heard in ways they previously had not experienced. Several expressed surprise and gratitude that their voices mattered, and I emphasized that their perspectives and experiences are critical, as they hold the key to driving meaningful and lasting change.

By collecting this data during my research project as an Interledger ambassador (and continuing to do so after), this work also has the potential to directly influence product creators and organizations as they refine existing tools or build new solutions. The goal is to encourage products that are developed with financially underserved communities and more closely aligned with their real needs, rather than based solely on assumptions or incomplete data.

As Interledger continues to expand its focus on financial inclusion in the United States, this research aims to identify key opportunities and gaps in the market. It can serve as a foundation for Interledger’s thoughtful expansion into a critically underserved space, where its technology and approach have the potential to drive meaningful impact.

Communications and Marketing

During my ambassadorship, I shared updates on my personal LinkedIn page, but since completing, nothing has been shared publicly. However, I will be publishing a data breakdown and a white paper on my fintech's parent company website, CREAMFactory.com.

What’s Next?

I plan to continue this research in 2026. While the specific cities have not yet been finalized, they are set to be confirmed by the end of February 2026, pending some partnerships and grants. In-person case studies are expected to take place between March and September 2026, with the next research update published by the end of the year.

I have already begun conversations with CDFIs and other organizations that have expressed interest in both the current and future findings. I will continue working closely with these partners to ensure the research informs meaningful, positive change in the digital financial inclusion ecosystem.

Community Support

Since I am continuing this work, I'd love to connect with anyone who works with or knows of organizations, fintech founders, and policymakers in the USA that focus on the financially underserved and the inclusion market, as I know this new perspective of backed data will make an impact.

Top comments (0)