Project Update

What is the informal economy in Europe, and how are they structured, formed, and understood by different communities who are involved in them? This was the major question that I kept coming back to in the past few months of research outreach. Despite this being the most basic question and the starting point of my research, the insights I gathered throughout my research and outreach process have continuously challenged my assumptions of what economic informality means in the European context. These assumptions not only challenge our understanding of the nature and scale of the informal economy, but also how digital financial inclusion can be done and strategized in our globalized world.

In the past months, I have conducted extensive literature research, mapped out diverse relevant civil society stakeholders, built 5 project partnership with NGOs, grassroot communities, and community-based organizations, talked to 20+ community leaders from civil society stakeholders who represent or work with 5 distinct communities who are often involved in the informal economy in Berlin and Madrid, with more talks and interviews being scheduled and conducted. In the project updates, I want to revisit some of the assumptions on informal economies and how they are challenged in the European context, with the case studies from Berlin and Madrid. By re-visiting these assumptions, I also start to rethink what strategies on digital financial inclusion can lead to a better world for those at risk.

To start with, I want to first give some context and background.

Informal Economy: What exactly do we mean?

Key Insights:

- Informal economy is economic activities, workers, and economic units that are, in law or in practice, not covered or insufficiently covered by formal arrangements.

- From the informal sector to the informal economy, the nature of the activities and their definition are defined in relation to the development of modern industrialized societies and capitalism.

The informal economy involves economic activities, workers, and units not fully covered by formal arrangements, like labor laws, social protection, taxation, and business registration.

The understanding of the informal economy has evolved through the work of organizations like the ILO and WIEGO, alongside academic contributions. Early ILO work focused on the informal sector as unregistered, unprotected enterprises. A significant shift in 2002 broadened the scope to the informal economy, encompassing all economic activities and employment relationships not adequately covered by formal arrangements, even within formal enterprises. The 2023 ICLS further refined this, focusing on “informal productive activities.” This evolution reflects a move from viewing informality as a characteristic of enterprises to recognizing it in diverse employment forms due to trends like globalized employment schemes.

Research directions distinguish workers and enterprises in the informal economies as they refer to different theoretical priorities and policy concerns. As my project focuses on labor rights and vulnerabilities in relation to digital financial inclusion, in this project, informal economies can refer to: informal workers, infrastructure in relation to informal economies, and informal economic activities, with formal-informal linkage being emphasized.

In this project, I focus on informal workers and infrastructure as a way to understand informal economies in Europe. Through my strategic outreach, I reach out to community leaders and civil society groups who are already representing the workers or working with the workers, instead of conducting direct interviews of the informal workers communities, as a way to create a larger impact, but also to protect the privacy and security of those informal workers who are in vulnerable positions. I study the overlap of financial and informal infrastructure through mapping and participant observation in field work in Berlin and Madrid, to uncover the hidden labor and unspoken part of the informal economies, and trace the mechanism and patterns of how the informal economies are constructed in the first place, and how the ecosystem can be maintained in the urban textures.

Formalization Debates

Key Insights:

- Formalization is controversial as it proposes dualism between the formal and informal economy; however still worth persuasion for labor right protection.

The term “informal economy” gained rapid support from development experts as a way to acknowledge the economic activities of the urban poor in the Global South. However, it soon faced criticism for being poorly defined, grouping diverse activities, creating a false dichotomy with the formal sector, and implying the latter's superiority. Anthropologist Lisa Peattie noted a cyclical pattern of criticism and redefinition, suggesting a shift towards comparative studies of specific economic institutions and policies instead of trying to refine the concept itself. This is exemplified in the Kenya report and the dualism it uses to describe Kenya’s economy.

Formalization debates are one of those long-standing debates that are a result of such critical reflection. Formalization is rather a controversial process among workers. The myth of formalization holds superiority over informal work in terms of labor conditions is not always true in all cases. Effective formalization should be multi-faceted, progressive, context-specific, and co-created with informal workers. Some scholars suggest alternative approaches focusing on reparations or improving informal work conditions without formalizing.

In Europe, however, the formalization debates vary from worker to worker, from community to community. While European regulations do not focus on formalization, informal workers are often those who are in vulnerable positions already. While formalization often can be seen as controversial for workers in the global south who are comfortable with their alternative economic structures and community-specific accountability mechanisms, formalization is indeed seen as a strategy to improve their vulnerable positions.

Berlin and Madrid as Case Studies

Berlin and Madrid are exemplary case studies for understanding the informal economy in Europe due to their roles as multicultural urban centers with dynamic migration patterns. They represent contrasting cases as major cities of Spain and Germany, respectively, also providing implications on the core and periphery of the EU, as they are located in Western and Central Europe, and Southern Europe. Spain and Germany both have significant informal economies, as Spain’s informal sector is estimated at 20.2% of its GDP and Germany’s informal sector is estimated at 11.7%.

These two cities are chosen for several reasons:

Similar patterns and conditions as migration societies;

A large part of vulnerable communities in the informal economy are people who identify as being part of different migrant communities. Spain and Germany share similar patterns and conditions as migration societies, with both urban impacts, labor market implications, and transnational networks created by migrant communities being particularly relevant and comparable.

Access to communities and emerging movements;

Communities in the informal sector are not the easiest to research about, due to legal contradictions, lack of trust, and fear from informal workers who are often in vulnerable positions, high risk in the empirical process, and often diverse political contexts these communities are subject to. The choice of case studies is significantly influenced by the existing access to communities through direct involvement with community work and activism in the past decade to support migrant, diaspora, and exiled communities in Germany & existing diaspora activists' network that links communities in Spain. In the past years, there have also been emerging groups and movements that connect diverse informal workers being built in Madrid and Berlin.

Regulatory differences and European implications;

Even though Germany and Spain are both subject to European-level regulations, they have different regulatory environments that impact the scale and nature of informal economic activities. The differences in labor market regulations, taxation policy, and administration, and overall regulatory quality provide implications for effectiveness and diverse ground realities regarding EU-level frameworks.

Bridging from these contextual backgrounds, I want to share some sneak peek of my initial findings through examining the five common assumptions of informal economies (Some of which I also used to believe, or are often assumed in research and advocacy around informal economies).

Assumption 1: Economic Informality Leads to Vulnerabilities

It is often assumed that economic informality leads to different levels of vulnerability. In my own project description, I wrote “economic informality leads to exclusion and precariousness”. This, however, sharply contrasts with how informal communities often frame the problem. "Informality” is not a problem to be solved: it is a symptom of many different hidden social, economic, and political problems. It is rather a two-way street: vulnerable conditions can lead to communities seeking informal economic activities as a way to repair, but such informal economic activities can lead to more positions of vulnerability, depending on local regulations, practices of law enforcement, and public perceptions of informality in different localities.

Implications on Digital Financial Inclusion Strategy:

We need to acknowledge that formalization and access to digital financial services do not always directly solve the problem for the vulnerable communities. An effective and community-centered digital financial inclusion strategy needs to be an active process of taking the existing vulnerabilities into account, which are often structural inequalities. Instead of plugging the digital financial services directly into vulnerable communities, the question can be how digital financial services can be used to solve barriers that are the result of larger contextual and structural issues: from lack of identification, to biased algorithms on money laundering, to bureaucratic hurdles in insurance.

Assumption 2: Communities Involved in the Informal Economy are Always Vulnerable

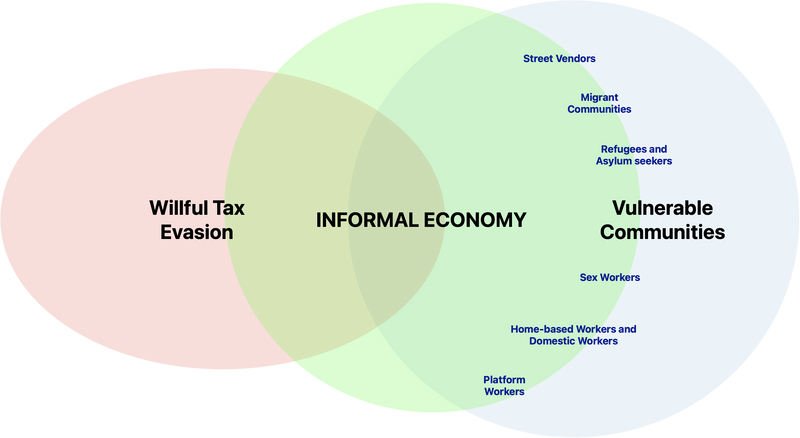

Informal economies are not exclusively composed of vulnerable communities, as is often presumed. While formalization policies and enforcement measures frequently focus on vulnerable populations—who indeed represent a significant proportion of informal economic participants—wealthy individuals and enterprises engaging in deliberate tax evasion also constitute a substantial share of informal economic activity and GDP. These actors are typically more difficult for authorities to detect and regulate. Moreover, community dynamics within informal economies can be complex; exploitation of informal workers may originate from influential or senior members within the same community. This is common among communities that experience different levels of social exclusion, which often reinforce hierarchical structures within the communities that further alienate certain groups from broader labor regulations and protections. This phenomenon is particularly prevalent in migrant communities. Ultimately, it is workers who possess pre-existing vulnerabilities that remain most at risk within the informal sector.

Implications on Digital Financial Inclusion Strategy:

For digital financial innovation to support inclusion, we need to be specific about which communities we are actually addressing. This is particularly important for the narrative shift in the political discourse around the informal economy. Which communities need to be included through digital financial inclusion work? And which groups of people are intentionally conducting evasion and exploitation? The answers to these questions often contradict the realities and have resulted in harm and distrust. Digital financial system design must be grounded in an awareness of the full spectrum of participants and complex community hierarchies in informal economies.

Assumption 3: Informal Economies are Hidden and in Shadow

Much of the research on informal economies has been conducted to understand the context of developing countries or the global majority economies, but from the perspective of the countries leading the economic globalization. The characteristics of informal economies in these contexts differ significantly from those in Europe, where informality was the norm; formalization is a process that accelerates due to industrialization and the rise of neoliberal capitalism. It is assumed that informal economies are hidden and in shadow, through taking the “formal economies” for granted. This assumption is not true in many countries around the world, as they are very visible and still constitute a large part of their economic structures. Through the research, I examined this assumption in the European context, and it is partially false. The vulnerable communities that are involved in the informal economy are often partially hidden: they hide their informal infrastructure. However, many groups who are involved in the informal economy are using the formal economy as the vehicle of their activities: subcontracting in the gig economy, for example. Existing financial infrastructure is their informal infrastructure.

Implications on Digital Financial Inclusion Strategy:

To support the digital financial inclusion of vulnerable communities involved in informal economies in whatever localities, the formal-informal linkage is an important research direction. As the formal-informal linkage often reveals layers of intentional exploitation versus structural exclusion. For example, strategies can focus on making mainstream digital financial products more adaptable and accessible to hybrid users, ensuring that compliance, onboarding, and transaction monitoring do not penalize or exclude those whose informal activities are intertwined with visible, formal systems.

Assumption 4: Civil Society Stakeholders Align on Values and Approaches in Supporting Communities in the Informal Economies

Contentions are everywhere, as it is assumed that business interests, regulators’ perspectives, and civil society often have differing positions on realities and strategies of inclusion. However, even civil society stakeholders have vastly contrasting approaches and values on how vulnerable communities in the informal sector can be supported. Is it more effective to mobilize social movements or resort to political negotiation within larger institutions? Shall we apply for this funding to support this group of people standing in front of us in need of urgent help, or shall we only do mutual aid, as the responsibilities that come from certain funding can pose restrictions on the work scope? Shall we join alliances that directly address the issues our communities are facing, or refuse to engage in knowledge politics that might lead to policing of communities in the long term? When there are vulnerabilities and risks, there is contention. This contention exists beyond the frames that we often assume. Supporting communities in the informal economy is one such case with a particularly high risk. This is exemplified in the continuous debates on sex workers’ rights and protection.

Implications on Digital Financial Inclusion Strategy:

Contentions are part of the process, coalition is more likely to build on assuming the best out of each other, and walk out of our direct alignment based on normative positions. Contentions exist because we are fighting against challenges in real people’s lives, and it proves that we care. Such tension shapes how digital financial products are designed, highlighting that the real challenge in digital financial inclusion is not just technical deployment, but managing the ethical and political contestations over data privacy, community autonomy, and the unintended consequences in technological development.

Assumption 5: It is Possible to Understand Economic Informality Locally

Similarly to our common assumption on hidden and shadow informality, there is an old image of the informal economy that is often highly connected to local textures and is done in analogue and local infrastructure. This is no longer true due to the accelerating development of the global platform economy, transnational networks, and human mobility. It is not possible to understand how the informal economy works and the conditions of the vulnerable communities in the informal economy through learning the regulations, social contexts, and infrastructure in one locality where they are currently operating. The relevant infrastructure, particularly for informal economic activities in Europe, has moved to digital platforms that are transnational. The relevant financial services and exclusions are also transnational. WeChat, for example, has evolved to be a major platform for informal economic activities for the Chinese diaspora and migrants; cycles of debts also very often start from the countries of origin for many migrant workers.

Implications on Digital Financial Inclusion Strategy:

In light of the transnational nature of contemporary informal economies, digital financial inclusion strategies need to extend beyond local or national frameworks and explicitly address the cross-border dimensions of financial access and exclusion. This requires designing digital financial services that can seamlessly operate across jurisdictions, accommodating transnational remittance flows, debt cycles, and digital platforms. Inclusion efforts should recognize that vulnerable communities in Europe’s informal economies often also rely on financial infrastructures rooted in their countries of origin, which shape their economic resilience and risks. To be more specific on potential pathways, for technologists and designers, digital financial tools may incorporate culturally and linguistically tailored interfaces that avoid harmful design patterns, interoperability with foreign financial systems which can potentially be enabled by Interledger Protocol, and policy practitioners may engage in global level policy work that advocates for protections against exploitative cross-border financial exclusion cycle.

Progress on Objectives, Key Activities

Connecting different movements and political communities

I have finished most of my literature research and interviews, and am still conducting ethnography of relevant infrastructure. I am progressing well in my civil society stakeholder mapping; the results will be organized and made available for the Interledger Community when the project is finished. I have identified some key communities and actors to engage with. In Berlin, this includes labor organizing communities (particularly the informal ones beyond the legal trade unions), migrant advocacy organizations, and Vietnamese communities and districts. In Madrid, this includes trade unions, migrant advocacy organizations, and Chinese communities and districts. I have engaged with all identified communities through informal discussion, semi-structured interviews, except for trade unions in Madrid so far. I have mapped out the academic and political discourse and relevant concepts, and tried to draw connections with these particular communities. For example, how is formalization perceived? What even is the informal economy? (Many communities do not know this term, as they have their own way of describing the nature of their labor) What is economic justice and empowerment? And what is financial right and financial justice?

Throughout my conversations with them, we have discussed the particular contexts of their communities, what financial technology and financial inclusion mean for them, and how the Interledger Ecosystem can potentially contribute to their work.

Capacity building for civil society actors, cultural workers, and grassroots initiatives:

I am in the planning process for this objective. I am currently building a partnership with Berlin-based organizations MigLab who connects migration and labor; educator, lawyer, and founder of Migrant*innen für Menschenwūrdige Arbeit and Delivery Charge Podcast Aju Ghevarghese John; and Banying, one of the oldest organizations in Berlin that supports female migrant workers who experienced violence. Through consultation and collaborative research and prototyping, we are gathering community insights and developing toolkits. In Madrid, I am in conversation with grassroots Chinese diaspora activists and Asociación Rumiñahui on further collaboration.

Outreach and dissemination targeting communities in the informal economy

I have not started with this objective, as this is the plan after the second objective is completed.

Key Activities Update

I have first been in the research process of reviewing literature, relevant debates, and existing work, and tried to draw connections between them with digital financial inclusion. I have finished a strategic outreach strategy based on my research.

I have progressed far in the empirical process: I have talked to 23 community organizers from different kinds, so far: they range from a co-founder of an NGO, to queerfeminist activists, to trade unionists, to artists who work with community mediation. I have done 6 recorded interviews so far.

My outreach has been progressing significantly: I am planning a group consultation session with project partners, and an in-person event in Berlin that invites the project partners to be in public conversation with each other on intersectionality in labor struggles and the relevance of inclusive financial systems in transnational labor.

I am now on a field trip in Madrid, conducting partly ethnography, and partly interviewing and meeting with potential partners.

Project Impact & Target Audience(s)

The project brings together civil society stakeholders, community leaders, and organizers from different informal workers groups: domestic workers, gig workers such as delivery workers, workers in the hospitality industry, migrant workers of different backgrounds (female workers who are victims of human trafficking, Chinese migrant communities in Spain, South Asian workers communities in Berlin...etc.) refugees, asylum seekers, and sex workers.

The project provides space for them to get connected and strategize together, connect diverse struggles, and raise awareness on their common struggles. They are often excluded and underserved in the current financial systems. Many of them are not often in conversation with each other, and are also not included in the political process that impacts their digital rights and financial rights as workers. The project emphasizes how an open-source and interoperable financial system is particularly important to improve their conditions and seek financial justice of these communities.

Communications and Marketing

I have not discussed my work in public, to my knowledge. I will think about it and do something in the future.

What's Next?

From Research to Community: Collective Imagination of Financial Justice

As the updates suggest, I am aiming to build trans-local communities that support the economic and financial justice of vulnerable communities involved in the informal economy. Several events are being planned in this direction. I need to also confirm and consolidate my connections with potential partners in Madrid.

From Community to Advocacy: Shifting Power from the Ground

The goal of the project is to leverage our collective knowledge production and newly built alliance to work together with the Interledger Ecosystem and shift power to the workers on the ground. This will include drawing from their insights to contribute to research reports and potentially policy advocacy outputs.

Community Support

At this point, I would particularly appreciate:

- I would be very grateful if anyone could give me feedback on the initial findings and assumptions on the informal economy: what do you think from your work’s point of view? Have you held these assumptions, or did you think differently? Does my implication on digital financial inclusion strategy seem realistic to you and your area of work?

- If anyone has knowledge on the technical and regulatory process of financial services in relation to informal workers and vulnerable communities in the informal economy, I would love to chat. I am particularly interested in relevant processes and cases on conditions of undocumented migrant workers and gig workers working under subcontracting, as they are the most relevant to the cases I am working around right now.

- I would love to start conducting more marketing and communication efforts regarding my project. If anyone has any contacts or strategies, I would love to learn from you! And as always, I am very often for a chat on your thoughts, ideas, and feedback on my project, no matter if it is relevant to the two points I mentioned above!

Additional Comments

I am extremely grateful for the last few months of support from the Interledger team, many insightful interactions that bridge a lot of my knowledge, and continuous learning on the Interledger Protocol.

Top comments (2)

Xiaoji - what a great report!! I will be in contact for marketing efforts

Thank you so much, Chiara! I really appreciate it! <3