The results of the first half of our research agenda have provided us with positive initial signs about the potential effects of the Web Monetization model on users’ mindful and socially conscious web browsing (see here, and here). Building on these results, we have designed and developed a setting to experimentally test the relationships between web monetization models, peoples’ values, and online content consumption choices. Our experiments demonstrate the effects of users’ awareness of online content monetization across multiple contexts, scenarios, and factors. We found that when users are aware that their online browsing provides monetary compensation to content creators, they prefer to consume content from non-profit organizations or independent creators and activists over that of mainstream media outlets.

Background and Theory

One of the most prominent characteristics of the web monetization model is, in our view, the fact that it increases users’ awareness of the monetization of their online browsing - for example, think of the “Coil is paying” badge. Our studies have, therefore, focused on examining the effects of increased awareness of online content monetization on users’ consumption choices. Our conceptual theoretical framework builds on theories from social and cognitive psychology, which have recognized people’s desire to maintain consistency with their values and behaviors (i.e., self-consistency (Lecky, 1945), self-perception (Bem, 1972), and cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957) theories). Our hypothesis, generally stated, is that increasing users’ awareness of the monetary support their online browsing provides to content creators will drive them to make content consumption choices that align with their values and beliefs. Our studies also contribute to the important ongoing debate on whether online activism is a complementary or rather a substitute for meaningful and impactful in-person activism (i.e., activism vs. “clicktivism” or “slacktivism”; Cabrera et al., 2017; Freelon et al., 2020; Gladwell, 2010; Morozov, 2011). We suggest that the Web Monetization protocol may be a solution that puts an end to this dilemma and be a welcome addition to any activist’s digital toolbox. Enabling creators to leverage their quality content to raise funds to promote their causes seamlessly and without using advertisement; and allowing users to contribute their time, clicks, and funds to creators who rally around specific causes. We assert that this could be closely related to the foot-in-the-door effect (Burger, 1999; Freedman & Fraser, 1966); a consequence of the desire to maintain self-consistency by which individuals are significantly more likely to comply with a substantial request after first agreeing to a minor request. We suggest that when browsing their favorite sites, Web Monetization / Coil users could be seen as already agreeing to comply with a small initial request, as their time on the site translates into monetary compensation to the creators. Based on the foot-in-the-door effect, we hypothesize that this makes them more willing to give out additional support to the creators or the causes being promoted. Furthermore, this effect is expected to amplify when users consume content by creators who are activists and promote social causes as they are driven by the motivation to avoid the cognitive dissonance between their existing beliefs and self-image and actions that may conflict with them - disagreeing to participate or provide additional support.

Experiments Design and Results

Our experiments were set to examine how increased awareness of online content monetization affects users’ consumption choices, and especially their preference between different types of creators (i.e., mainstream media outlets vs. non-profit organizations vs. independent bloggers and activists) and with relation to their own values, beliefs, and personal connections. Specifically, study one examined the effects of monetization awareness on preference for co-partisan sources (i.e., sources that are aligned with the viewer’s own political preferences) and for non-profit organizations vs. mainstream media, and study two examined the effects of monetization on the preference for independent video creators and activists (“vloggers”) vs. mainstream media.

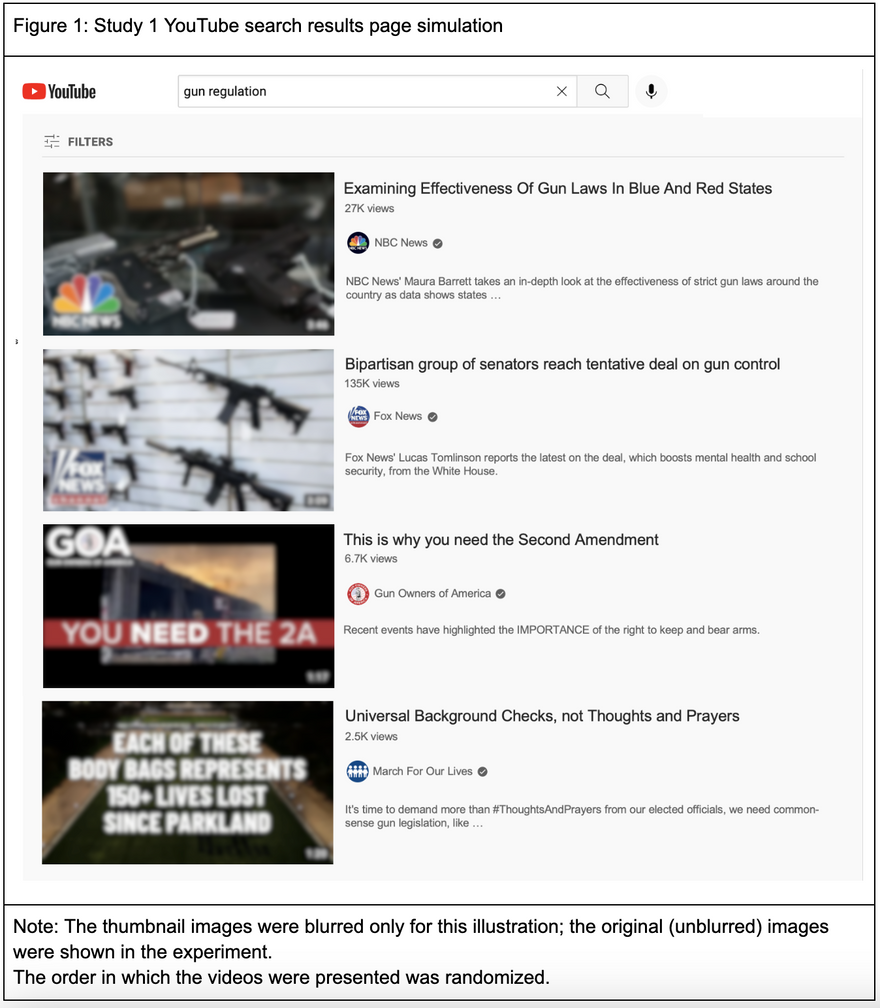

Both studies included two groups: a treatment group for which we included questions designed to increase participants' awareness of the monetization of content on the YouTube platform; and a control group in which participants answered similar questions minus the ones intended to increase monetization awareness. We measured the effects of the treatment by observing participants’ choice of video to watch from a simulated YouTube search results page, and given a specific scenario (e.g., to learn more about “gun regulation” (study one; see Figure 1) or about “disability rights” (study two)). We also measured peoples’ willingness to provide additional support by asking whether or not they would be interested in learning how they can support a non-profit organization (relevant to the topic of the video they chose to watch) (see “methodology” section below for further details on the experiments’ design).

Study 1: politically polarizing context - preference for mainstream media vs. non-profit organizations

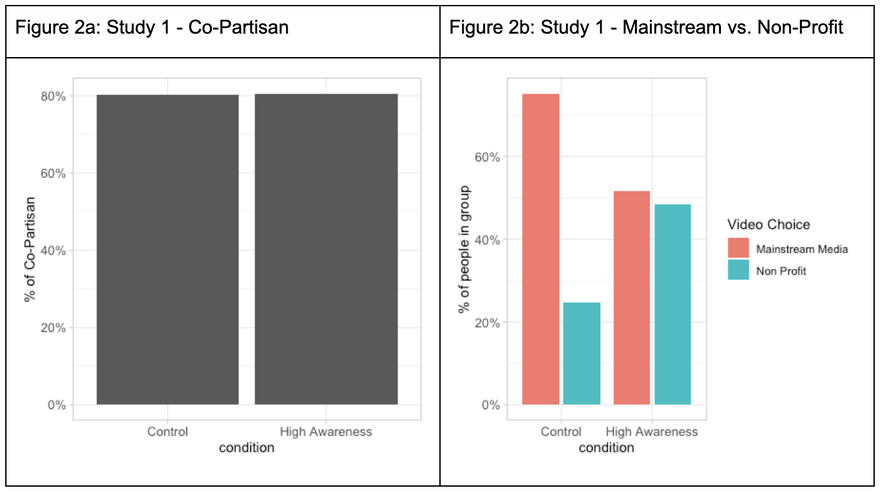

Overall, the results of study one show that increasing users’ awareness of the monetization of online content indeed affects their consumption choices. We first examined the effects in relation to users’ political preferences. We found that users’ choice of co-partisan sources was almost identical across the two conditions (78.1% in the control group and 77.9% in the treatment; see Figure 2a). A reasonable explanation for the lack of effect in this measure is that the initial rate of co-partisan preference is so high that what we observed here is a ceiling effect. Next, we looked at the effect of monetization awareness on the choice between mainstream media outlets and non-profit organizations. As shown in Figure 2b, the results clearly show that the percentage of people who chose to watch a video from a non-profit organization doubled when users’ awareness of monetization was raised (from 24.8% in the control group to 48.4% in the treatment group). This difference is also highly statistically significant (p < .001). Overall, we learn that monetization awareness drives people to support organizations that match their political stance. Thus supporting our hypothesis that increasing users’ awareness of the monetary support their online browsing provides to content creators, will encourage them to make content consumption choices aligned with their values and beliefs.

Additionally, we examine the effects of monetization awareness and content consumption choices on users’ willingness to provide additional support. The results here were mixed. While there was no direct effect of the treatment on participants’ compliance with the request for additional support (28.6% of positive responses in the control group and 29.5% in the treatment group), we did find that those who chose to watch a video from one of the non-profit organizations were also more likely to agree with the request for additional support (37.5%) as compared with those who watched one of the mainstream media videos (24.2%). This difference was statistically significant (p < .05), providing some support to our hypothesis on the self-consistency effect.

Study 2: neutral context - preference for mainstream media vs. independent creators / activist

The second study was intended to build on the results of the first and extend them. We were interested in studying these questions in a neutral, non-political context and with additional types of online content creators. The experimental design was similar to the one used in study one. The main difference was the use of a different scenario and a different set of videos in the YouTube search results simulation. For the neutral context, we used the topic of “disability rights and living with disability”. Instead of comparing the choice between mainstream media and non-profit organizations, we had participants choose from a pool of mainstream media videos and videos created by independent vloggers (video bloggers) and activists. Additionally, we had participants answer a short open-text question explaining their choice of video.

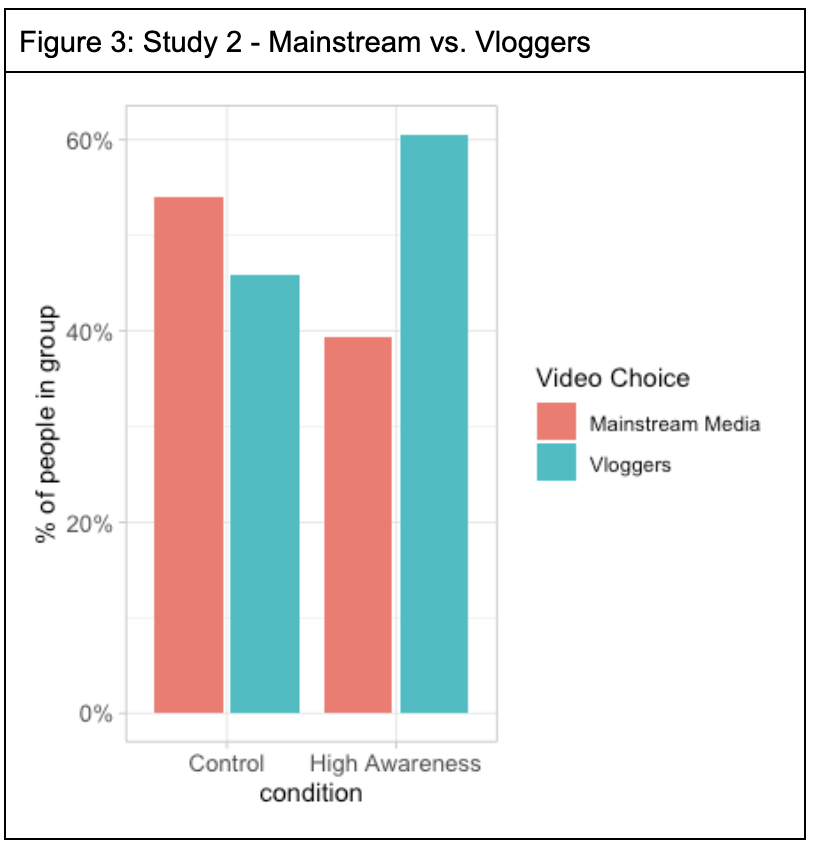

The results show again how increasing people’s awareness of monetization changes their online content consumption choices. Preference for the videos by independent vloggers and activists increased from 45.9% in the control condition to 60.6% in the treatment condition (p < .05). Furthermore, this effect was also reflected in participants' explanations for their choices. For example: “I think she [the vlogger] will benefit more from me watching her video, rather than ABC.”; “I chose the video that interested me the most and I also chose the video from a smaller creator because I would like for them to get the money from the ad, if possible.”; and “Initially I chose CNN but figured the individual channel needs my views”.

With regards to the effects on users’ willingness for additional support, the results were again inconclusive. We observed a slight (not statistically significant) negative effect for the treatment, and an increase in compliance (also not significant) among the people who chose to watch the independent creators' videos.

Methodology

Study 1

Participants were recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk and told that the objective of the task was a survey about online media usage and preferences. They were randomly assigned to either a treatment (“High Awareness”) or a control group. The survey began with questions regarding participants' usage and familiarity with various online news and media platforms. Importantly, one of the questions was designed to increase participants’ awareness of the monetization of content on YouTube. This question was presented only to those in the treatment group. In contrast, participants in the control group answered a similar question that did not deal with monetization.

Next, participants were directed to a page that simulates a search results page on YouTube for the query “gun regulation” (see Figure 1). The page included four relevant videos whose sources were either right-leaning (Fox News, Gun Owners of America) or left-leaning (NBC News, March For Our Lives). The videos were also differentiated based on whether they were from a mainstream media outlet or a non-profit organization. Participants were instructed to imagine they were interested in learning more about gun regulation. Then, they were asked to choose the video they would like to watch and instructed that they would be asked about the content of the video. Participants’ choice of video to watch is our primary measure of the effect of monetization awareness on content consumption. Participants then watched the video they chose and answered questions regarding its content.

Next, we presented each participant with information regarding one of the two non-profit organizations - Gun Owners of America for those who chose to watch one of the right-leaning videos and March For Our Lives for those who watched the left-leaning videos. Participants were asked if they would like to learn how they could help support that organization. Their answers to this question allowed us to measure the effect on their willingness to provide additional support.

Study 2

The design of study two was very similar to that of study one. It differed mainly in the content of the simulated YouTube search page. In study two, we presented a page that simulates a search for “disability rights and living with disability”. We, again, presented four videos as the results of the search. However, instead of mainstream media and non-profit organizations, we had mainstream media and independent creators and activists (“vloggers”). The mainstream media outlets included PBS News, CNN, The Wall Street Journal, and ABC News (a random selection of two for each participant). The vloggers included videos by Annie Elainey, Sitting Pretty Lolo, Zack Collie, and Freddo the Wheelchair Guy (YouTube channel names; again, two of the four were randomly selected to be presented). Another difference from study one was the inclusion of the open-ended question “Why did you choose this video” directly following the participants’ choice of video watch. Lastly, the non-profit organization used in the request for additional support was the Disability Rights Fund.

References

- Bem, D. J. (1972). Self-Perception Theory. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 1–62). Elsevier.

- Burger, J. M. (1999). The Foot-in-the-Door Compliance Procedure: A Multiple-Process Analysis and Review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(4), 303–325.

- Cabrera, N. L., Matias, C. E., & Montoya, R. (2017). Activism or slacktivism? The potential and pitfalls of social media in contemporary student activism. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 10(4), 400–415.

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford university press.

- Freedman, J. L., & Fraser, S. C. (1966). Compliance without pressure: The foot-in-the-door technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4(2), 195–202.

- Freelon, D., Marwick, A., & Kreiss, D. (2020). False equivalencies: Online activism from left to right. Science, 369(6508), 1197–1201.

- Gladwell, M. (2010, September 27). Small Change. The New Yorker. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/10/04/small-change-malcolm-gladwell

- Lecky, P. (1945). Self-consistency; a theory of personality. Island Press.

- Morozov, E. (2011). The net delusion: The dark side of Internet freedom. PublicAffairs.

Top comments (0)